There’s a glaring contradiction in today’s economic discourse, and it clouds the investment outlook. The loudest voices warning about America’s unsustainable federal deficit are often the most reflexive critics of tariffs, an essential tool that could help address the crisis. They demand “fiscal responsibility” but fall silent when asked what they’d cut from the budget. Suggest entitlement reform, and they’ll tell you it’s political suicide. Propose higher income taxes, and they bristle at the economic drag. Ask how they’d raise $2.0 to $2.8 trillion annually to close the federal budget gap, and the conversation ends.

That’s why tariffs—unfashionable, imperfect, and deeply misunderstood—may be one of the only practical tools left that can meaningfully address the deficit until the country is ready for major changes to how the government collects revenue and spends.

D.O.G.E. Promised a Trillion-Dollar Fix. It Delivered a Rounding Error.

The Department of Government Efficiency (D.O.G.E.) was supposed to be the bold solution to government waste. Originally pitched as a vehicle for cutting $1 trillion in inefficiencies, the agency—backed by Elon Musk and restructured under President Trump—quickly revised expectations downward to $150 billion. D.O.G.E. operates as a consultant would, examining costs and structure and recommending changes to achieve efficiencies across various departments.

D.O.G.E. impact is a subject of some debate. As of mid-2025, D.O.G.E. has claimed between $150 billion and $ 90 billion in savings, although independent audits dispute much of that figure. More troubling, aggressive cuts to revenue-generating agencies like the IRS reduced government income. By some estimates, DOGE’s efforts may have cost taxpayers $135 billion through re-hires, overtime, legal settlements, and lost tax collections.

While well-intentioned and fundamentally a good idea, the shortfall was a strategic failure that exposed the limits of the “cut spending” approach. D.O.G.E. aimed to trim fat but ended up delivering a rounding error instead of transformational change.

Growth Alone Won’t Save Us

With a less-than-spectacular D.O.G.E. impact, and large Government spending cuts off the table — at least for now — the bipartisan default in Washington has long been to grow the economy and let increased tax receipts shrink the deficit as a percentage of GDP over time. It’s an appealing theory that consistently fails in practice. Despite periods of strong GDP growth, federal spending continues to outpace revenue by unprecedented margins.

While the growth strategy is politically palatable and will help over time, the U.S.’s current fiscal situation, with annual deficits of over $2 trillion, is dire. We don’t have the luxury of waiting for growth to solve a crisis that compounds daily. Growth matters, but it’s not enough. We need substantial revenue, and we need it soon.

Understanding Tariffs: A Tax, Not Inflation

Let’s address the elephant in the room: tariffs are, in fact, a tax. But they are emphatically not inflation.

Inflation is a monetary phenomenon—the expansion of the money supply that dilutes currency value and drives broad-based price increases. Tariffs don’t expand the money supply or devalue the dollar. They are a targeted consumption tax applied to imported goods, with three key differences from domestic taxes:

- Revenue generation: Unlike inflation, tariffs generate federal government revenue, potentially $300 billion annually

- Targeted impact: They affect specific imported goods rather than the entire economy. Imports are roughly 15% of the U.S.’s GDP today.

- Importer and Corporate absorption possibility: Who absorbs the cost increase from U.S. tariffs is an interesting and complex question, with the absorbing party differing by item and by importer. With energy costs roughly 10% lower than two years ago, many corporations have absorbed most of the tariff costs rather than passing them through

Despite persistent warnings from economists, tariffs have not triggered the runaway inflation they predicted.

The Hidden Costs of Corporate Absorption

However, when corporations absorb tariff costs, the economic impact doesn’t simply disappear—it gets redistributed. Companies facing compressed profit margins from tariff absorption experience a cascade of effects that ultimately flow back to the broader economy:

Reduced profit margins lead to lower corporate earnings, which translate to decreased stock valuations. This creates a diminished wealth effect as portfolio values decline, prompting consumers to reduce spending. Meanwhile, lower capital gains tax revenue partially offsets the government’s gains in tariff income.

This redistribution means that while tariffs may not be directly reflected in consumer prices, their costs still flow through the economy via financial markets and reduced economic activity.

The Regressive Reality of “Targeted” Impact

While tariffs don’t affect every sector equally, describing their impact as merely “targeted” obscures an important truth: if passed through, they disproportionately burden lower-income households. These families spend a higher percentage of their income on goods (versus services), have less flexibility to substitute away from imported products, and are more price-sensitive to increases in everyday items.

This regressive effect means that tariffs could function as a consumption tax that hits hardest those least able to absorb the cost—a significant trade-off that must be weighed against their revenue-generating potential. Kitchen table economics won 2024 for the Republicans, but it could be the reason they lose the 2026 midterm elections.

Why Income Tax Hikes Hit a Wall

One truism of taxes: Anything you tax, you get less of. That reflects human behavior and rational economic actors. Raising income taxes sounds straightforward until you encounter the Laffer Curve’s hard ceiling. Beyond a certain point, higher rates reduce total tax revenue by discouraging work, saving, and investment. Historical data suggests we may already be approaching that point, considering total income taxes collected rose when Trump dropped rates in his first administration.

The federal government’s share of GDP rarely exceeds 20%, regardless of marginal tax rates. Taxing productivity has diminishing returns and penalizes the very economic activity we need to encourage. Tariffs, conversely, are harder to avoid and don’t punish domestic output. For revenue generation with minimal collateral damage to productivity, tariffs offer a superior approach, though they come with their own distributional consequences.

Tariffs as Statecraft: Economic Leverage Without Bloodshed

One of tariffs’ most under appreciated benefits is their geopolitical utility. Unlike sanctions or military action, tariffs exert pressure with fewer human costs and less international conflict.

Consider Canada’s Digital Services Tax proposal earlier this year, which targeted U.S. tech firms. The Trump campaign’s swift threat of retaliatory tariffs prompted Canada to reverse course within days. No troops, no diplomatic standoff—just credible economic pressure accomplishing what traditional diplomacy might have taken months to achieve.

In an increasingly multipolar world where military intervention grows costlier and less popular, tariffs represent a powerful, non-violent tool of statecraft.

The Mainstream Economics Blind Spot

The loudest tariff opposition comes from economists who forecasted a Great Depression during COVID, predicted inflation was “transitory,” and missed nearly every major market rebound of the past five years. Now they’re warning of recession if tariffs increase.

Perhaps they’re right this time. But their track record suggests their models are shaped more by ideological assumptions than empirical evidence. As investors and fiduciaries, we must remain disciplined and objective, recognizing that markets rise under both Democratic and Republican administrations because innovation and capitalism transcend partisan politics.

A Nuanced Approach: Targeted Implementation

Smart tariff policy requires acknowledging both benefits and drawbacks. The mainstream economic consensus identifies legitimate concerns: tariffs can raise consumer prices, potentially trigger trade wars, and may reduce competitive pressure on domestic industries.

The solution isn’t to abandon tariffs but to implement them strategically:

Who are the most inelastic exporters?

What option do they have? Early returns on inflation and the “Liberation Day” April 2, 2025, tariffs reveal higher government revenues and little to no increased inflation or inflation expectations. This result goes against conventional economic groupthink and needs further exploration. One idea is that exporters where trade deficits are large and long running are “inelastic” and as a result have little recourse but to absorb the tariffs if they wish to continue their export volumes.

Target critical industries:

Focus on sectors vital to national security—steel, defense, critical minerals, and advanced manufacturing—rather than blanket applications that raise consumer costs across the board. Tariffs have an additional “incentive impact,” where importers may choose to build plants and manufacture in the U.S., thereby avoiding the tariff cost altogether. This is not a simple calculation for these importers as U.S. production costs could be higher, negating the profitability improvement from moving production to the U.S..

- Use as negotiation tools: Follow the US-China Phase One trade deal model, leveraging tariffs to secure better terms while avoiding long-term economic fallout.

- Maintain policy clarity: Rapid shifts create business uncertainty that kills investment. Clear, consistent policies allow markets to adapt and plan accordingly.

- Match unfair practices: When trading partners engage in dumping or subsidization, targeted tariffs can level the playing field without escalating broader tensions.

- Open new markets to U.S. exporters: One of the goals of recent tariff policy has been to open up agricultural markets to U.S. exporters, and this could have a beneficial impact on U.S. agricultural producers and exporters.

The Implementation Gap

However, a significant disconnect appears to exist between this strategic approach and current practice. The administration has largely deployed blanket tariffs across broad categories, including items that the U.S. cannot efficiently produce domestically, such as coffee, bananas, and numerous other products. This approach is a shock-and-awe approach to international trade, and if the intent was to draw everyone’s attention to this issue, the approach succeeded. Unfortunately, this approach creates exactly the problems that strategic implementation could avoid: higher consumer prices on necessities, economic inefficiency from protecting non-strategic industries, and diplomatic tensions without clear negotiating objectives.

This gap between theory and practice undermines many of the arguments in favor of tariffs. The current approach resembles less a surgical instrument and more a blunt tool, impacting the U.S. investment landscape as we saw in the April-May timeframe and making it harder to achieve the revenue and strategic benefits while minimizing economic disruption.

Trump 2.0: Tariffs as Economic Policy

In his first term, Trump deployed tariffs more surgically, targeting China, steel, and automotive sectors. In his second term, tariffs are expected to anchor his economic strategy alongside tax cuts, deregulation, and energy dominance.

The Trump approach may be unpredictable, but it’s not irrational. His focus on significantly altering the terms of U.S. trade across all trading partners can provide near-term economic growth. The mixed stock market performance that we have seen since April 2 creates a dynamic that appears to be high risk, high reward in terms of effective policy implementation. Tariffs can help the Trump administration achieve its objectives. Trump seeks a legacy of bringing industries back to the U.S., delivering on his promises of higher real wages to blue-collar workers, resulting in a booming economy. The question is how far he can take this fundamental restructuring of U.S. trade relations without incurring significant international and domestic opposition.,

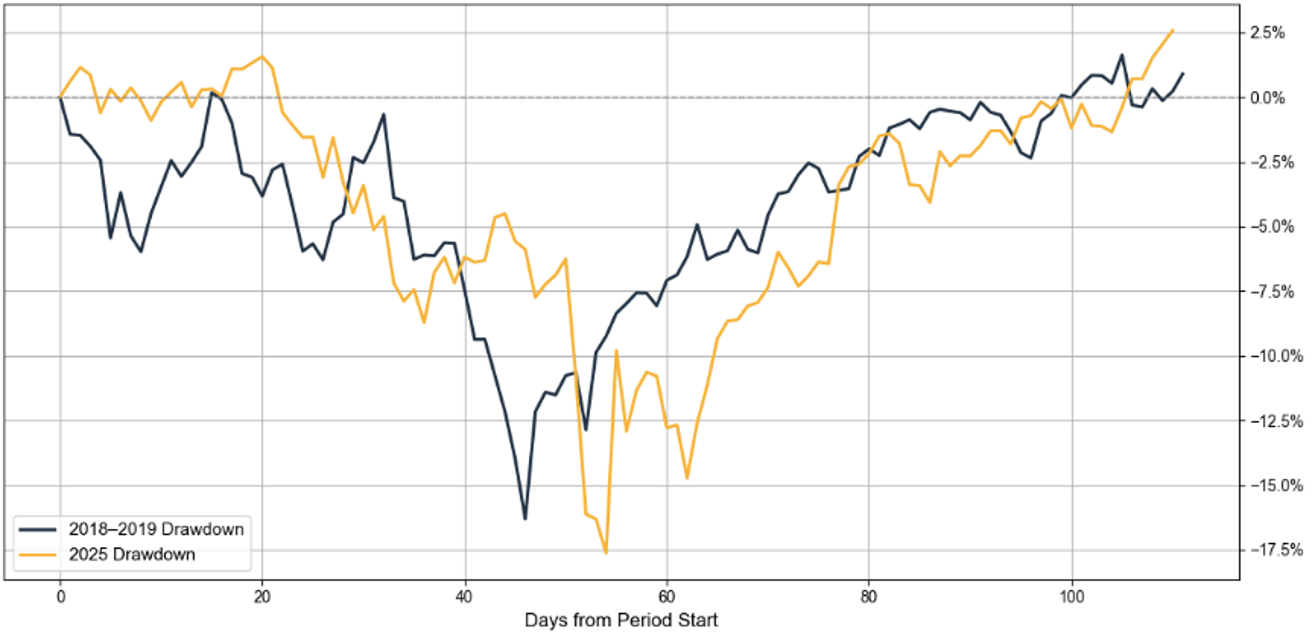

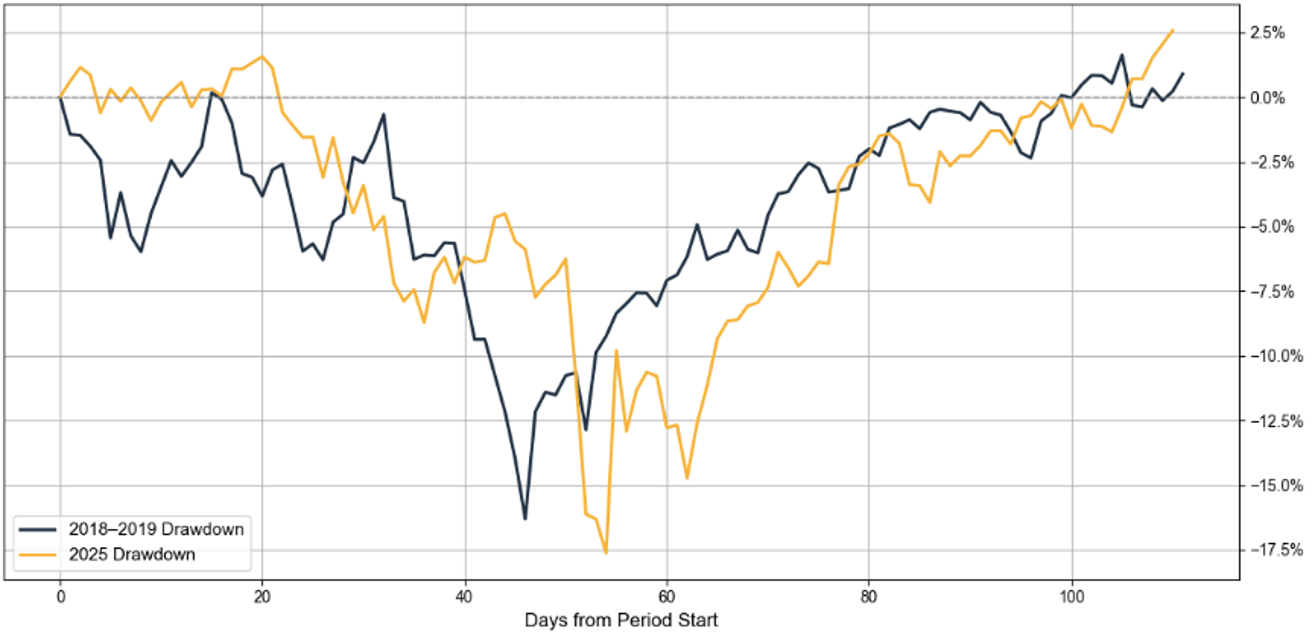

Markets Recover From Tariff Shocks

History offers a perspective on tariff-related market volatility. In April 2025, markets dropped 19% on tariff news—eerily similar to December 2018’s 19% decline over trade tensions. In both cases, markets recovered as investors recognized the temporary nature of the disruption. Both recoveries were swift once investors had better visibility into the impact and scope of the tariffs on industries and trading partners.

This pattern suggests markets can adapt to tariff policies more readily than economists predict, especially when those policies generate tangible economic benefits. The chart speaks for itself:

I am proud of the Gatewood Investment Committee and its successful navigation of the market correction this year. On the morning of April 7th, when the market was at its low point for 2025 (easy to see this in hindsight, hard at the time), our CEO said the following to our advisors at our Monday morning all-hands meeting:

“I would keep some powder dry. Since 1957, we’ve had 12 corrections in the S&P 500 greater than 20%. Assuming we’re in a bear market now, half of them were between 20-30%, three were between 30-40%, and another three were greater than 40%. If you have a lot of cash, don’t overcomplicate it. Invest half now, another quarter at a 30% drop, and go all-in, buying everything you can at a greater than 40% drop. You might only get one or two opportunities at that level in your lifetime.”

–Aaron Tuttle CFA® CFP® CLU® ChFC® | Partner | Chief Executive Officer

Since April 7th, the S&P 500 has risen by over +25%. Our clients are the beneficiaries of our continued commitment to long-term, methodical investing on their behalf. That’s the Gatewood way.

The Bottom Line: Tariffs May be the Only Tool We Have Left

We can’t cut our way out of this deficit at least for now, D.O.G.E. proved that. We can’t tax our way out through income taxes—the Laffer Curve won’t allow it. We can’t inflate our way out without destroying the currency. And while growth will certainly help, our fiscal situation requires exploration of all possible revenue sources.

That leaves tariffs as one of our most viable short-term options for meaningful deficit reduction until the country is ready for major changes to how the government collects revenue, what services it provides its citizens, and the cost of those services.

Tariffs have the potential to generate substantial revenue, though with significant distributional consequences. Tariffs create geopolitical leverage. Tariffs can strengthen strategic industries when properly targeted. The impact of tariffs may fall unequally on exporters, importers, nations, and consumers. They offer a possible path to start closing the deficit before it reaches crisis levels.

The key is honest acknowledgment of their costs and who absorbs these costs: the regressive burden on lower-income households if passed through, the hidden effects of corporate absorption flowing through financial markets, the impact on exporters and importers, and the critical importance of strategic rather than blanket implementation.

You don’t have to love tariffs to recognize their potential impact as a bridge solution until the country is ready for significant changes to how the government collects revenue and spends. At this point, they represent one of the only tools with a credible shot at improving our fiscal trajectory before time runs out, provided we implement them thoughtfully rather than as a blunt instrument.

The deficit is the fire. Tariffs are the hose. But we need to aim carefully, or we risk dousing the wrong things while the real problem continues to burn.

Curious About the Counterpoint?

Read Gatewood CEO Aaron Tuttle’s perspective on why tariffs might distract from the real work of fiscal reform.

Important Disclosures:

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly.

Investing involves risk including loss of principal. No strategy assures success or protects against loss.

The economic forecasts set forth in this material may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

This information is not intended to be a substitute for individualized tax advice. We suggest that you discuss your specific tax situation with a qualified tax advisor.

There is no guarantee that a diversified portfolio will enhance overall returns or outperform a non-diversified portfolio. Diversification does not protect against market risk.

The S&P 500 Index is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.